Ralph Rugoff’s curation of the 58th Biennale involved the entire art world in what today is certainly a globalising issue: May you live in interesting times. A title drawn from an English expression wrongly attributed by certain British politicians to an ancient Chinese curse, alluding to periods of crisis, uncertainty and disorder; “interesting times” as, indeed, the times we are living.

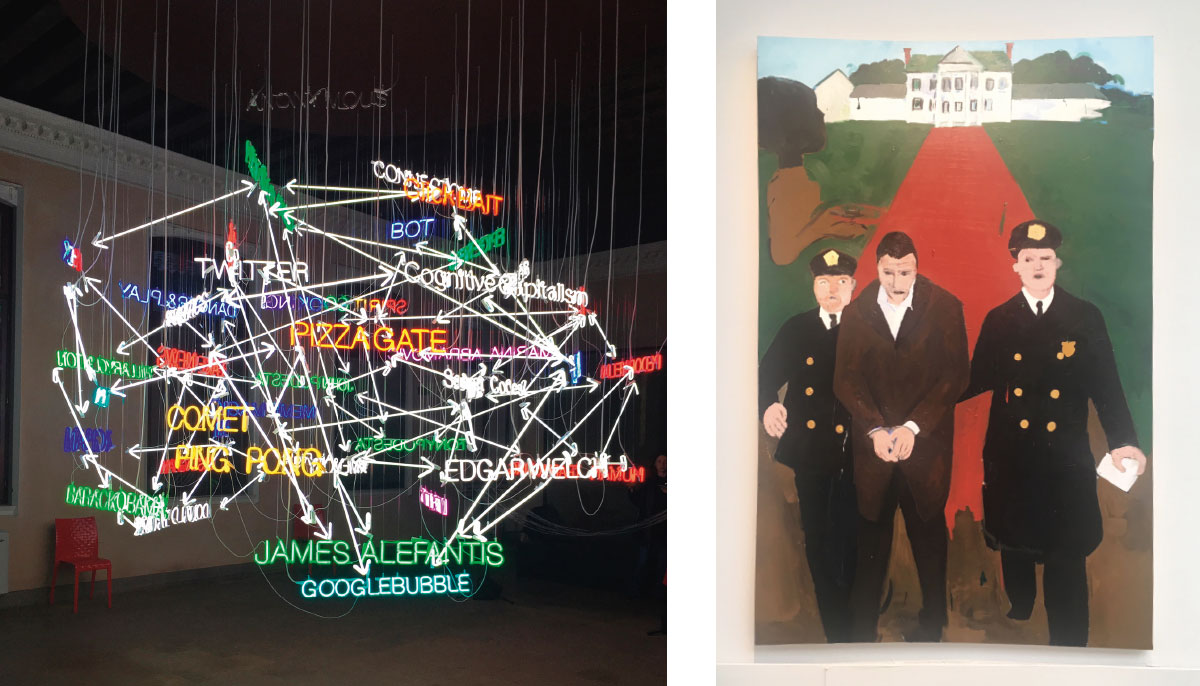

Right: Henry Taylor

Right: Henry Taylor

We all know that the emerging economies are the largest consumers of the kind of new millennium technology that’s come to dominate virtually everything today, and this finds obvious confirmation in the fact that of the seventy or so artists only twenty are European. Without a shadow of doubt the artistic involvement was global, as indeed global was the involvement of technology, so, yes, the artists kept to the theme proposed by the curator, but there is something of a historical but…. Technology is cold and doesn’t speak to the heart of its users, and this Biennale doesn’t speak to the heart but offers a cold, detached narrative of the times of our times, the moment we live.

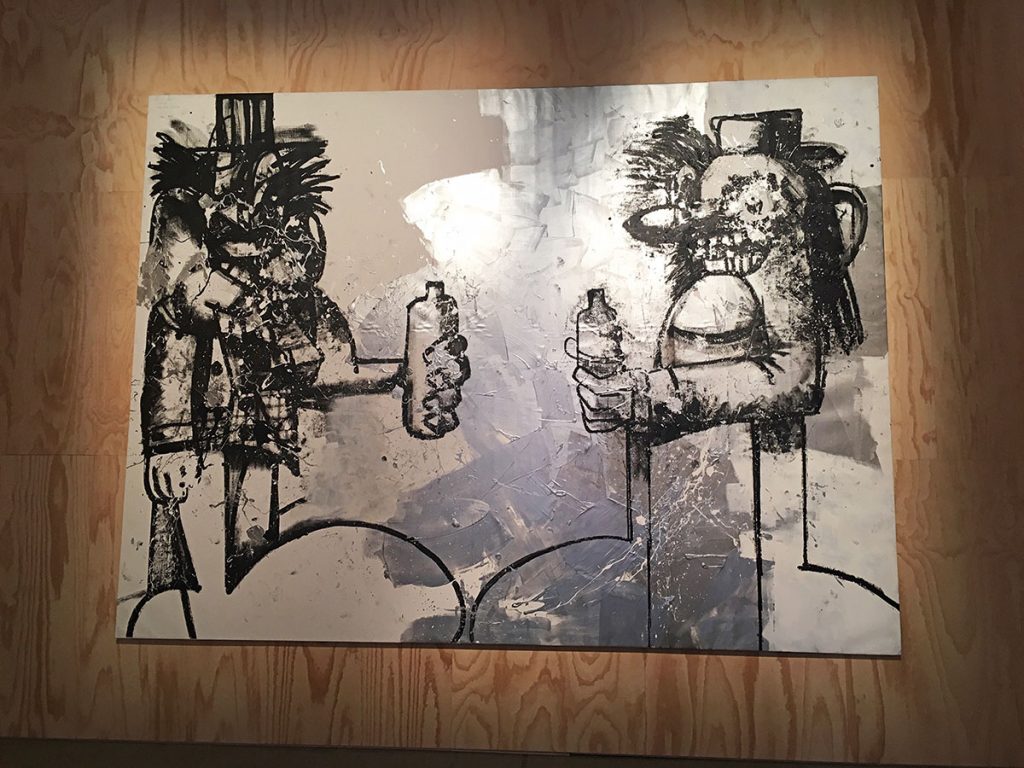

Left: Nabuqui

Left: Nabuqui

Since time immemorial artists have offered an expression of their experience: their surroundings, the tragedies and hopes of their everyday existence and their dreams, as a gift to the future, and they did it with different media: painting, sculpture, drawing and others, like photography and video, but almost always with poetry. I feel this Biennale will be remembered as being the one without poetry.

The entry ’overture’ is played by Chinese artists Sun Yan and Pen Yu’s Cant’ Help Myself and here, both in the Giardini and in the Arsenale we encounter enormous videos, cybernetic installations and giant-size sculptures that remind us of, and in effect almost are the billboard images that technology bombards us with every day everywhere we are. I’d much rather have seen an artist on one of those massive posters they used to paint by hand, than the enormous bright screens there: it would’ve been a more poetic encounter, rather than leaving the feeling of being unwitting contributor to an enormous electricity bill caused by the excessive consumption of energy.

But…while of the highly involving there was little, I would recommend a visit to the Serbian pavilion, for a harmonic immersion into an elegant dialogue between painting and sculpture, the Argentinean pavilion, that feels like a browse through the diary of a felicitous passage on an adventure in contemporary life, and the Russian pavilion, to witness a theatrical piece of grand effect with nostalgic references to Rembrandt and Rodin. But perhaps the most involving experience is the Brazilian pavilion, where photographs and videos captivate us in street dances that give hope for the soul of future youth through music and dance, one of the few notes of hope in this Biennale steeped as it is in a sense of sad precariousness, into which the world of our times has led us.

Left: Kiefer / Right: Baselitz

Left: Kiefer / Right: Baselitz

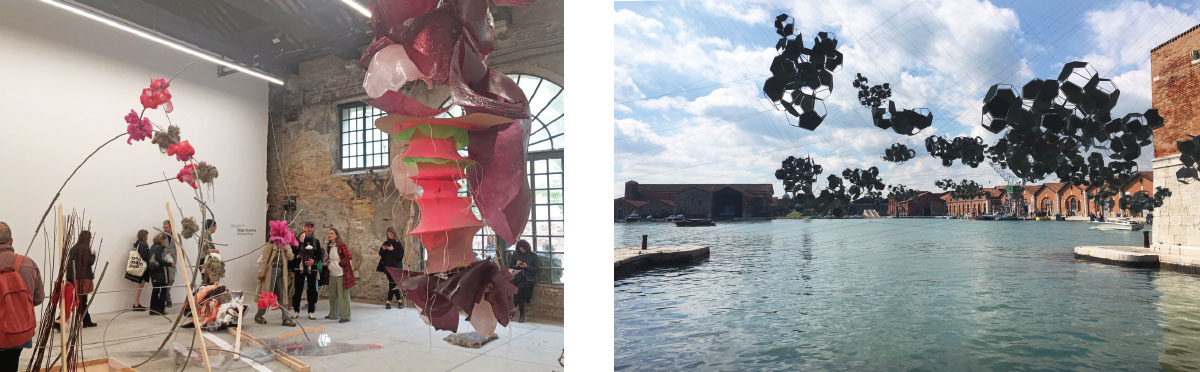

The only notes of poetry are Thomas Saraceno’s fascinating installation at the Arsenale and, at the Giardini international pavilion, the robot armed with a huge brush sweeping up what looks to all intents and purposes like blood, to the horror of the onlookers: a romantic auspice for the return of the art of painting.

At Palazzo Molin it’s worth seeing part of a private collection that’s just materialised in the Lagoon, to admire a sensational Kiefer.

Right: Thomas Saraceno

Right: Thomas Saraceno

Fortunately Venice herself offers us an involving immersion in great painting: Burri at the Cini Foundation, Baselitz at Galleria dell’Accademia, Frankenthaler at Palazzo Grimani and Gorky at Cà Pesaro, all absolutely not to be missed and who give us all hope for the future we so need.