If there can be no doubt that the fashion world in recent years has been beset by a stylistic cliché rich in ruffles, frills and embroidery, overlapping intertwinings, multicolour sequins and feathers, patterns and quotations, there are still those who pursue the ideal of a timeless harmonic and balanced elegance. More considered, more personal. A line of thought that resonates in a vocation to abstraction, a conceptual, sublime cleansing. Nothing is harder to achieve that apparent simplicity. And this concept is incarnate in the fatal creed of Mademoiselle Coco, who dictatorial, declared: “Elegance is frigid”. Re-paraphrasing this concept of hers, we could easily follow it with yet another brilliant affirmation, namely that “in any item of apparel there’s always something you have to take off”.

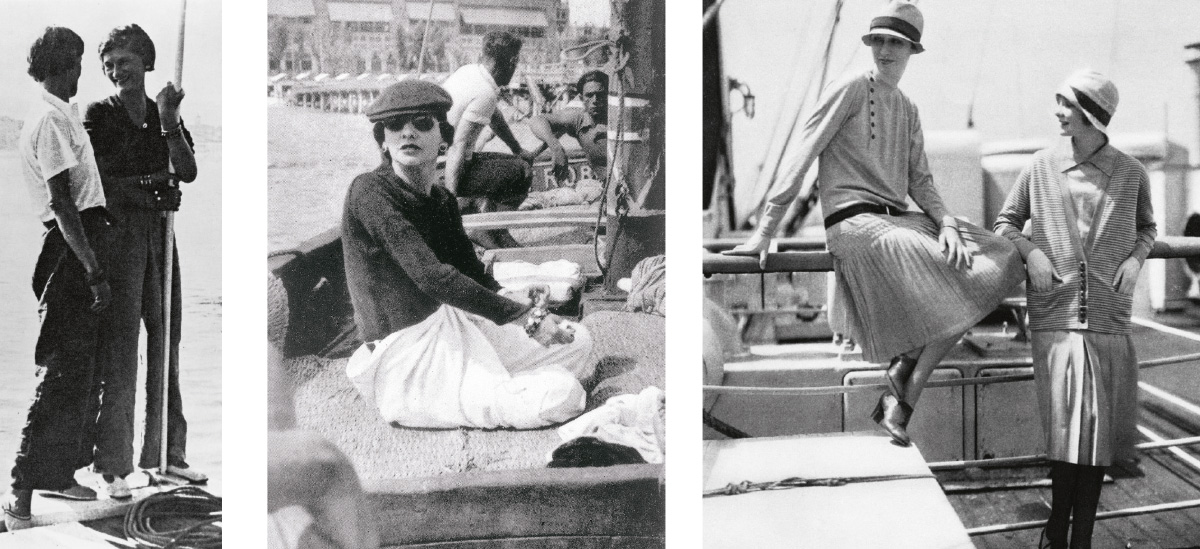

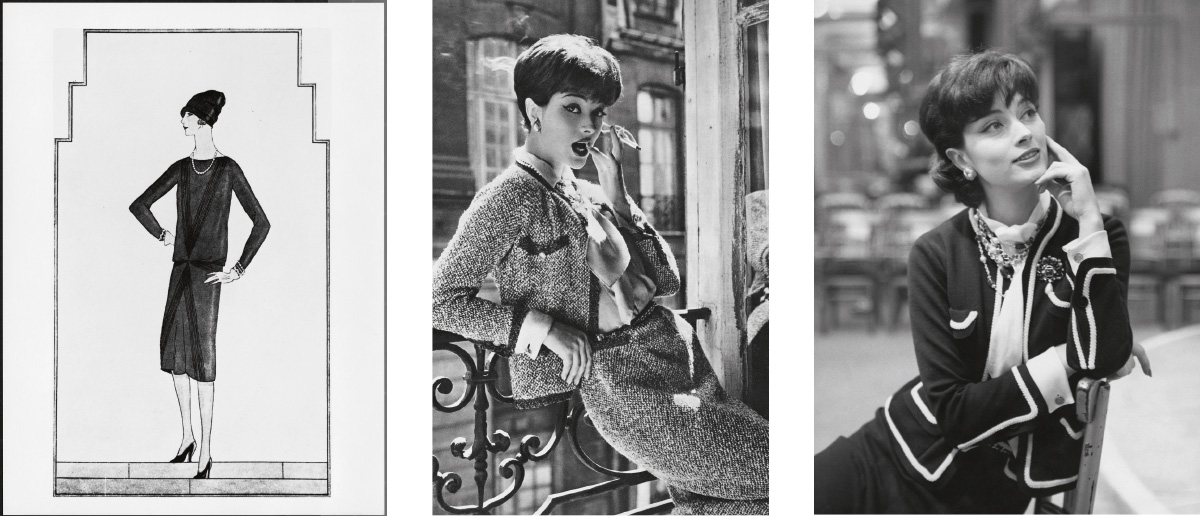

Chanel’s ideas are almost too well-known: her revolution has straddled the modernisation of womankind’s image, stemming from the ingenious inventions of the first three decades of the 20th century: a sportswoman, a woman living a man’s life,

a woman who rides and races, competes and sunbathes, a woman who wears trousers on the beach and anywhere else, who cuts her hair abandoning the age-old plait and previous century hairdressing and who, thereby, lives the modern life.

All this is expressed in the progressive dynamic of subtraction, the mantra of the absolute identification of a concept to be declined in an aesthetic vibration projected into the future. It is hard, and takes an enormous effort, to chisel out a form, hone it to its essence, outline its profile and give body to it with confidence, without any need to disturb its intimate original shape.

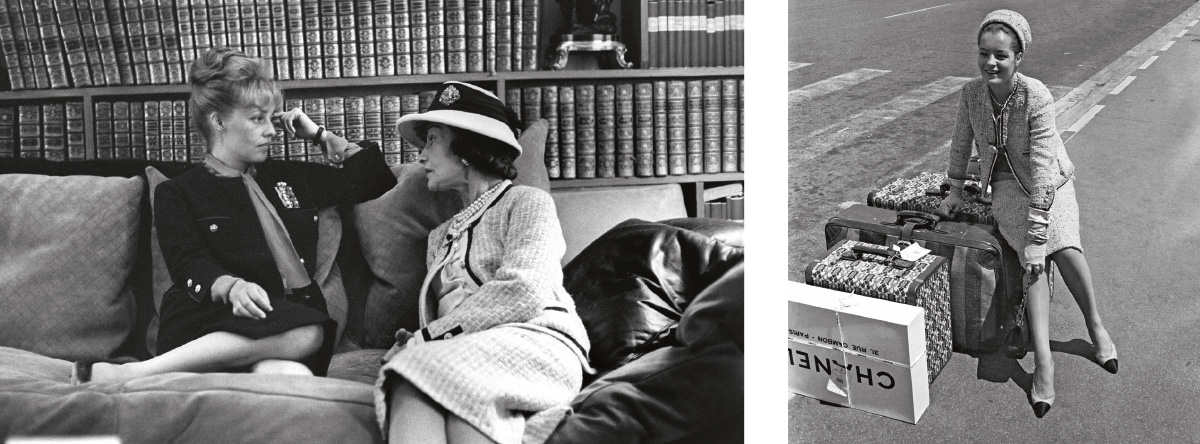

Precisely from the weave of the Scottish tweeds she fell in love with while in the company of the Duke of Westminster Hugh Richard Arthur Grosvenor, better known as Bendor, in 1954 she created the classic Chanel suit, bordered in black with metal lion’s head buttons or softened by pearls and gold chains that became her distinguishing mark, along with the camellias.

A flop for the press, except for the Americans who sensed how revolutionary it was. Grace Kelly, Ingrid Bergman, Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider, Catherine Deneuve all fell in love with it.

Today only the celebrities have changed (Victoria Abril, Gwyneth Paltrow, Tilda Swinton and Cara Delevingne, to name but a few), but the legend of an item every woman wants to wear still remains.

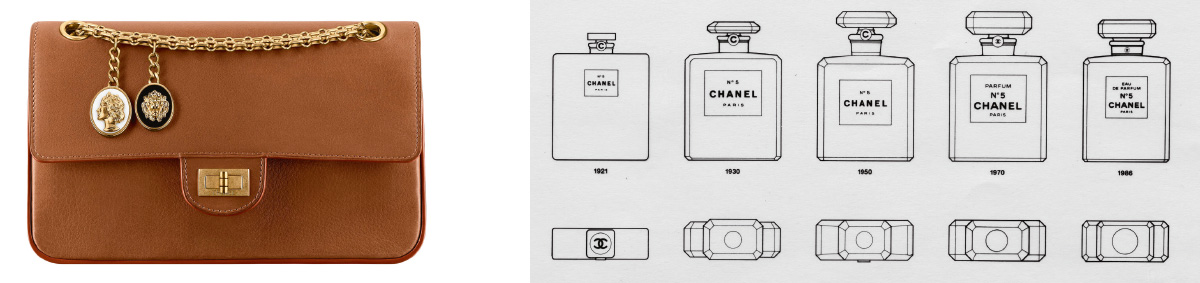

It was Coco who introduced to fashion a soft, revolutionary (in terms of performance) fabric like jersey. And it was she who transformed accessories into jewels and jewels into accessories; she invented the first ever logo, the double ‘C’. Chanel created perfumes that have conquered the world and that are still amongst the best sellers today. First and foremost the legendary No. 5: in an era in which fragrances were just a mixture of natural vegetable and animal essences, she trusted in the research of Ernest Beaux into aldehydes, synthesised products, effective and costly, and he proposed a range of new, strange combinations, each of which he gave a number.

For her use of humble materials and for the inspiration she drew from the figures of a working life, Chanel was crowned queen of the genre pauvre, of a sort exceptionally modern and snobbish “poverty of luxury”. The icon of this style being the black turban, absolute evergreen of every modern woman’s wardrobe.

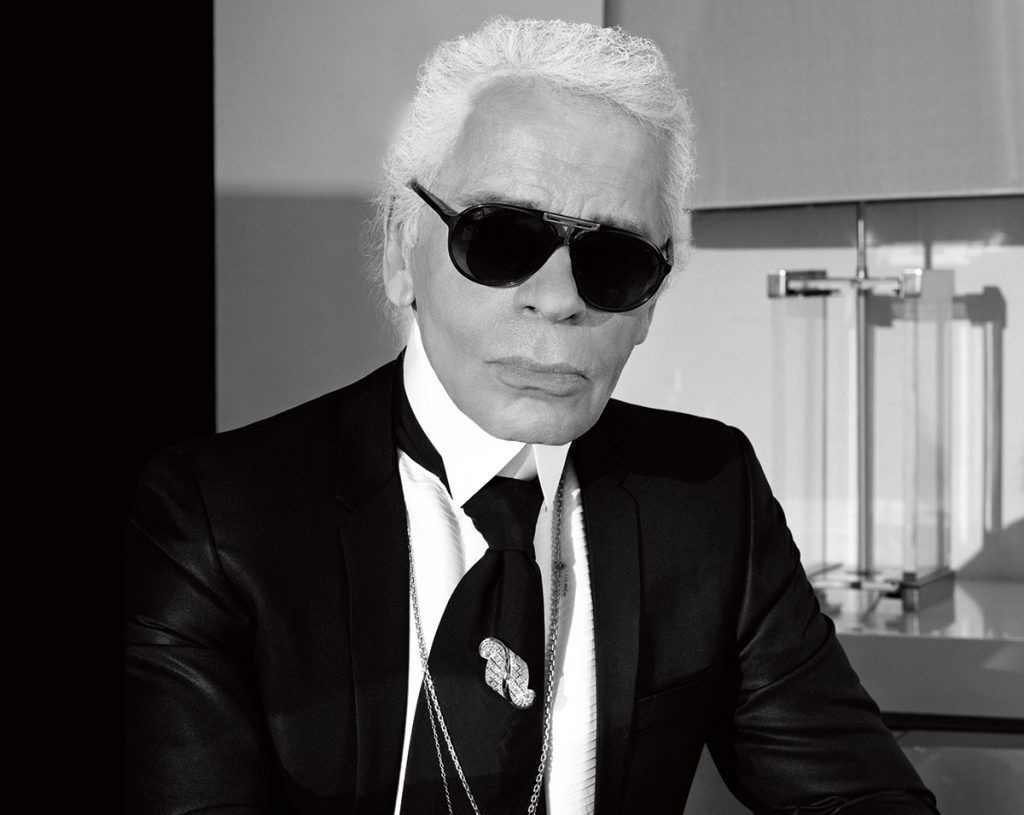

Standard elements proposed since time (almost) immemorial by the magic touch of Karl Lagerfeld, since 1983 committed to “creating a better future – as he wrote, quoting Goethe – with the elements left by the past”.

This is the premise for the F/W 2016-17 collection, presented at the Grand Palais, which the creative genius of Karl Lagerfeld has gradually transformed into a true set, with gardens brasserie, airports. A celebration of the tradition of the Rue Cambon label that continues onto the runways. With the symbol of the house like a symbol of power. Tweed suits, contrasting borders, camellias even on the pants. Figures stretch and skirts open with invisible zips revealing side splits, marrying with equestrian quotations and jeans decorated with the chalks of an artisan tailor. And the pearls, embroidered onto light dresses, even on the buttoned hat band. They’re enchanting. A purist hedonism. Or pure hedonism. In an aesthetic collisions that happily celebrates a concept: Chanel essentials.

A manifesto that meets the equally fundamental choice of colour, the net symbolism of a chromatic suggestion. A minimalism, no longer absolute but rather entirely original, faithful above all to the particularity of the fabrics, the perfection of the cuts, the balance of the plays on volumes. A style that generates good taste. An eternal, indispensable value. The mark of virtuous mastery and freedom from the slavery of time.

All this explains the decision to present the Cruise collection 2017 on a Caribbean island. There could be no better backdrop, in effect, than the avenue separating Central Havana from Old Havana to set off the captivating look of Coco Cuba. With its tree-lined avenues, colonial buildings and four bronze lions that – lo and behold – recall the animal chosen by M.lle Chanel as her iconic emblem, not to mention her zodiac sign.

The boulevard, listed as a UNESCO World heritage site, revealed itself as a truly spectacular location. Aboard variously coloured vintage convertibles, the staff of the show landed on the set in a triumph of tourists and habaneros, injecting new lymph into a decadence that the explosion of aromas, colours and innate Cuban calor exalt with special suggestion. Accompanied by a live background of traditional island melodies, Karl Lagerfeld “narrated” a fascinating pre-revolutionary Cuba, animated by intellectuals and movie stars of the calibre of Hemmingway and Ava Gardner. On the runway, impalpable circle skirts alternate with masculine baggy-trouser suits, midi-skirts, pencil dresses in the colours of the Cuban flag and T-shirts blazoned with “Viva Coco Libre!” in a triumph of dazzling colours, sequins and flounces enhanced by accessories and distinctly Cuban headgear like the Hemingway style panama, the Che beret and the Guayabera shirt. And striking details: maxi Cadillac-pattern ties, clutches inspired by the island’s famous cigar, two-tone lace-ups and sophisticated strings of pearls that underscored the ‘fifties mood pervading the entire collection.

Substantial details, personal marks, capable of narrating fashion in all of its contemporary condition for the exaltation of its sheer presence. What’s exciting is that it makes simply being seem like the creative avant-garde marking the coming future, conquering the indifferent inertia of time.