The apparent contradictions of Umberto Boccioni: extremely personal – and somewhat irreverent – considerations on the life and work of one of the giants of Italian Futurism.

The municipality of Milan marks the centenary of the death of Umberto Boccioni with an exhibition at Palazzo Reale.

Over recent years much has been written about this artist, augmenting his fame and bringing to light numerous aspects of his private life and his role in the most significant artistic current of the twentieth century: Futurism.

Perhaps for this very reason another article commenting the exhibition, or yet another critique of Futurism could be considered superfluous: just about everything that can be has already been written and explained by experts far better prepared than yours truly …

All I can really do is offer a sincere account of the emotions that Boccioni has always aroused in me, a few “words in freedom” about he, for me more than any other, who incarnated the contradiction present in every artist, between their proclaimed ideals and the real content of their works and lives.

Perhaps more than his companions in art, Umberto Boccioni was the paradigm of the complete artist: academic, graphic artist, painter and sculptor. Art impregnated his entire existence and threw those of many of his contemporaries into confusion, in a period of intense contrasting energies, in a Europe in constant turmoil.

In the end, Boccioni was fortunate enough to die at the beginning of one of the conflicts that according to the futurists should have represented the “world’s only hygiene” (art. 9 of the Futurist Manifesto – 20 February 1909).

In effect, by staying alive he would most probably have had the chance to give the world other masterpieces, but he would have had to come to terms with the evidence that war has never been the “hygienic” solution to any problem.

And thus, “death in war”, the glorious epilogue of an existence in total coherence with his ideals, is the first of Umberto Boccioni’s many contradictions.

LEFT: Umberto Boccioni, Carica di lanceri, 1915 – Tempera, vernice, collage su carta intelata, 334 × 503 mm / Milano, Museo del Novecento, Collezione Jucker // RIGHT: Umberto Boccioni, Elasticità, 1912 – Olio su tela, 100×100 cm / Milano, Museo del Novecento, Collezione Jucker

No glorious end in battle for him … Boccioni didn’t even live to see the war.

Indeed he died most unluckily while training: a mere riding accident (another symbol of speed – protagonist in many of his paintings). What’s more, the cause of the fall wasn’t caused by a steed launched at full gallop, but a horse practically standing still: the artist fell just after passing a level crossing!

This precise episode – bitter and ironic at the same time – whetted my spirit of observation, making me notice many other contradictions present in the artist, both artistic and otherwise.

BOCCIONI AND WOMEN

The conclusion of the aforementioned Manifesto’s article 9 speaks explicitly of “scorn for women”. Boccioni had portrayed women since his very first works: his mother, his friend Ines (at a sewing machine, how banal!)… and did so with a tender, loving, sentimental approach. Technical research into lines in motion, waves, the wind in the hair, highlights the turbulent thoughts of those young women, the bitter reflections of those age-old preoccupations for their sons at war. It doesn’t matter that the illustrative detail is swept away by the impetuous, rapid stroke of the brush … Boccioni is a blatantly sensitive person, sincerely involved by his feelings for the women in this life.

LEFT: Umberto Boccioni, Studio di testa (La madre; Dimensioni astratte), 1912 – Olio e tempera su tela, 60 × 60 cm / Milano, Museo del Novecento // RIGHT: Umberto Boccioni, Romanzo di una cucitrice, 1908 – Olio su tela, 150 x 170 cm / Parma, Collezioni Barilla di Arte Moderna

BOCCIONI AND ILLUSTRATIVE TECHNIQUE

Speed, speed, speed!!! The word is shouted, screamed by the futurists whenever they can! But the reality of painting teaches us that the studio of a work takes time: observation, conception, sketches… Throughout the exhibition we stand in admiration before sketches of landscapes, and in the artist’s diaries we read that he spent three hours, standing, to draw just a few lines on a sheet no bigger than a postcard.

BOCCIONI AND THE CLASSICS

The futurists’ attack of the classics is frontal.

On the contrary, in Boccioni’s diaries we read words of great admiration for the past masters. The concept of pictorial perfection was an obsession for him. He saw Giambellino’s “La Pietà” and wrote: “I saw a picture that made my eyes become moist. It’s sheer perfection. An artist dream can go no further. It has everything. It is terrifying.” Then once again that irony of life pops up imperturbable: a century on from his death, how would Boccioni have reacted to hearing himself defined as a “classic”?

LEFT: Giambellino, Pietà, 1470 – Tempera su tavola, 86×107 cm / Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera // RIGHT: Umberto Boccioni, Antigrazioso, 1912-1913 – Olio su tela, 80 x 80 cm / Torino, Fondazione F.C. per l’Arte

BOCCIONI AND THE MUSEUMS

“We want to destroy the museums!” (Futurist Manifesto, article 10).

Fortunately they didn’t succeed and today, precisely in the museums he purported to destroy, we can admire all of his magnificent works!

LEFT: Umberto Boccioni, Figura, 1915 – matita nera, inchiostro nero a penna e pennello, acquerello, tempera e collage su carta, 562 × 390 mm / Milano, Civico Gabinetto dei Disegni del Castello Sforzesco // RIGHT: Umberto Boccioni, Unique forms of continuity in space, 1915

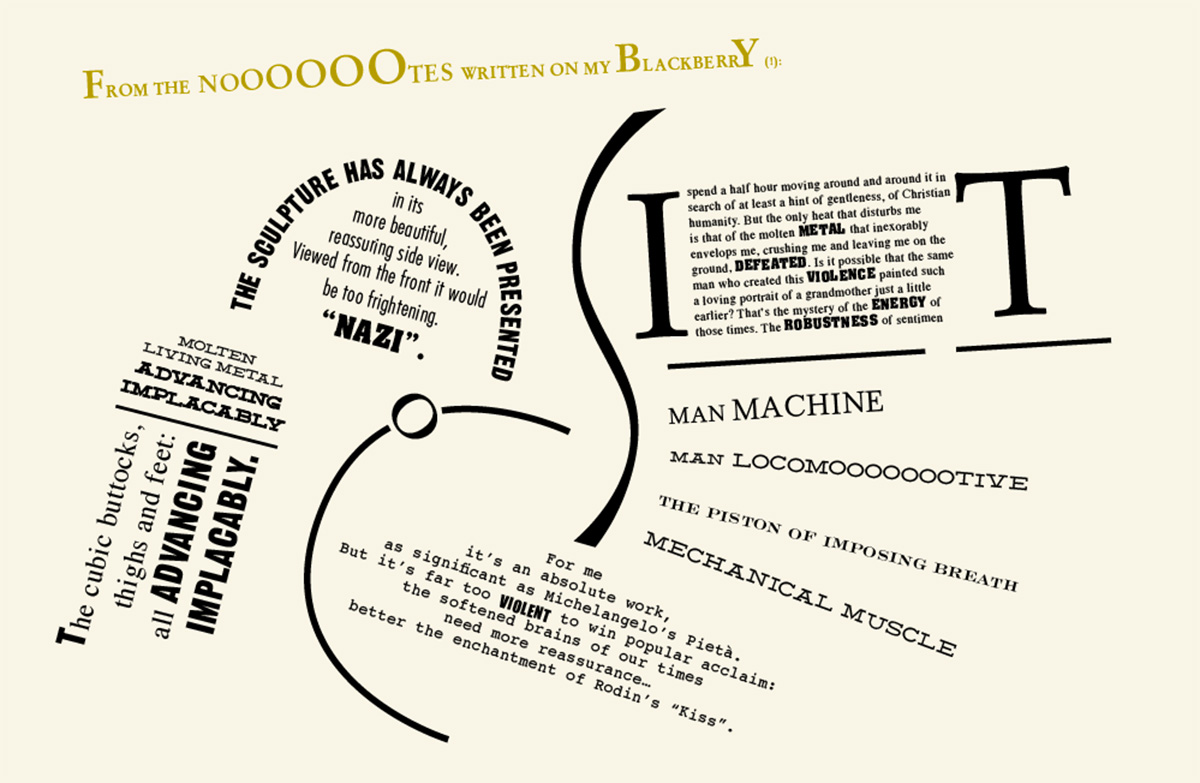

To conclude this mosaic of thoughts, expressed perhaps a little irreverently, I’d like for offer a few of my notes, decidedly more serious and respectful, on his most representative and undoubtedly coherent sculpted works: “Unique forms of continuity in space” (1913).